[Excerpt from Trying to Stop a War in 1939 (includes verbatim reproduction of 122 documents in their entirety included in the British Foreign Office report Miscellaneous No. 9 (1939) Documents Concerning German-Polish Relations and the Outbreak of Hostilities between Great Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939).]

[Excerpt from Trying to Stop a War in 1939 (includes verbatim reproduction of 122 documents in their entirety included in the British Foreign Office report Miscellaneous No. 9 (1939) Documents Concerning German-Polish Relations and the Outbreak of Hostilities between Great Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939).]

Timeline to War:

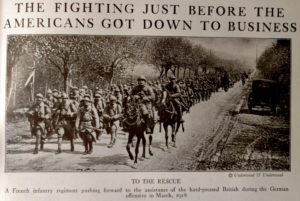

Our story begins in 1934 when Germany and Poland signed an Agreement, valid for ten years, to resolve all matters between them in a peaceful manner. Hitler even went so far as to compliment Poland as “the home of a great, nationally-conscious people.” But by 1939 Hitler had changed his tune and no longer wanted peace so much as he wanted more territory. He had already militarized the Rhineland in 1936, annexed Austria and the Sudetenland in 1938 and the rest of Czechoslovakia in 1939. Now he wanted Danzig and a route and railway through the Polish Corridor. Poland turned to Great Britain for help and Hitler resented the interference. And that was just the beginning.

January 1934 to January 1939 – Initial positive German-Polish relations

The governing factor in the relations between Germany and Poland during this period was the German-Polish Agreement of the 26th January, 1934 (See No. 1 below). This agreement, which was valid for ten years, provided that in no circumstances would either party “proceed to the application of force for the purpose of reaching a decision” in any dispute between them. In the five years after the signature of this pact Hitler made a number of speeches friendly to Poland (Nos. 2-8).

Poland was “the home of a great, nationally-conscious people” (21st May, 1935). It would be “unreasonable and impossible,” so Hitler acknowledges, “to deny a State of such a size as this any outlet to the sea” (7th March, 1936). The agreement “has worked out to the advantage of both sides” (30th January, 1937).

March 15, 1939 – Deterioration in European situation resulting from German action against Czecho-Slovakia

The position after the German occupation of Czecho-Slovakia was summarized in speeches by the Prime Minister at Birmingham on the 17th March (No. 9) and by Viscount Halifax, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in the House of Lords on the 20th March, 1939 (No. 10).

Mr. Chamberlain described the German occupation as “in complete disregard of the principles laid down by the German Government itself,” and asked: “Is this the end of an old adventure, or is it the beginning of a new? Is this the last attack upon a small State, or is it to be followed by others?”

Lord Halifax stated that the action of the German Government was “a complete repudiation of the Munich Agreement and a denial of the spirit in which the negotiators of that agreement bound themselves to co-operate for a peaceful settlement.”

On the 23rd March the Prime Minister stated in the House of Commons that His Majesty’s Government, while not wishing “to stand in the way of any reasonable efforts on the part of Germany to expand her export trade,” was resolved “by all means in our power “to oppose a “procedure under which independent States are subjected to such pressure under threat of force as to be obliged to yield up their independence” (No. 11).

In a conversation of the 27th May between Sir Nevile Henderson, His Majesty’s Ambassador in Berlin, and Field-Marshal Göring, the Ambassador warned the Field-Marshal that Great Britain and France would be involved in war with Germany if Germany attempted to settle German-Polish differences “by unilateral action such as would compel the Poles to resort to arms to safeguard their independence” (No. 12).

April to May 1939 – German-Polish discussions

“In a speech to the Reichstag on the 28th April, Hitler announced that he had made proposals to the Polish Government that Danzig should return as a Free City into the framework of the Reich and that Germany should receive a route and railway with extra territorial status through the Corridor in exchange for a 25-year pact of non-aggression and a recognition of the existing German Polish boundaries as “ultimate.” On the same day a memorandum to this effect was given to the Polish Government.

“The German proposals, which had been presented for the first time on the 21st March 1939, i.e., less than a week after the German occupation of Prague were now described as “the very minimum which must be demand from the point of view of German interests.” Hitler also claimed that the German-Polish Agreement of January 1934 was incompatible with the Anglo-Polish promises of mutual assistance and therefore was no longer binding (Nos. 13 and 14).

On the 5th May the Polish Government replied to the German Government with an explanation of their point of view. The Polish note repeated the counter-proposals which the Polish Government had put forward as a basis for negotiation in reply to the German proposals, and refuted the German argument that the Anglo-Polish guarantee was in any way incompatible with the German-Polish Agreement (No. 16). The Polish Minister for Foreign Affairs elaborated his country’s case in a speech made in the Polish Parliament on the 5th May. The Minister said that the Polish Government regarded the German proposals as a demand for “unilateral concessions.” He added that Poland was ready to approach “objectively” and with “their utmost goodwill” any points raised for discussion by the German Government, but that two conditions were necessary if the discussions were to be of real value: (1) peaceful intentions, (2) peaceful methods of procedure (No. 15).

The Polish memorandum reminded the German Government that no formal reply to the Polish counter-proposals had been received for a month, and that only on the 28th April the Polish Government learned that “the mere fact of the formulation of counter-proposals instead of the acceptance of the verbal German suggestions without alteration or reservation had been regarded by the Reich as a refusal of discussions” (No. 16).

Anglo-Polish Agreement

On the 31st March, the Prime Minister announced the assurance of British and French support to Poland “in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence, and which the Polish Government accordingly considered it vital to resist” (No. 17). An Anglo-Polish communique issued on the 6th April recorded the assurances of mutual support agreed upon by the British and Polish Governments, “pending the completion of the permanent agreement” (No. 18). The Agreement of Mutual Assistance was signed on the 25th August. The articles defined the mutual guarantee in case of aggression by a European Power (No. 19).

April to June 1939 – Developments in Anglo-German relations and in the general British attitude towards the international situation

Anglo-German as well as German-Polish relations deteriorated after the German occupation of Czecho-Slovakia. On the 1st April Hitler made a speech at Wilhelmshaven in which he attacked Great Britain and British policy towards Germany, and attempted a justification of German policy (No. 20). Hitler spoke in the Reichstag on the 28th April announcing the denunciation by Germany of the Anglo-German Naval Agreements (No. 21).

On the 27th April a memorandum to this effect was sent to the British Government (No. 22). On the 16th June Viscount Halifax again denied to the German Ambassador in London that Great Britain or any other Power was “encircling” Germany (No. 23). A week later (23rd June) His Majesty’s Government sent a reasoned protest to the German Government denying the validity of the German unilateral denunciation of the Anglo-German Naval Agreements, and also refuting the arguments of fact (i.e., persistent British hostility to Germany) by which Hitler attempted to justify his denunciation of the Naval Agreements (No. 24).

In view of these facts and of the increasing international tension, Viscount Halifax took the opportunity, in a speech at Chatham House on the 29th June, to define at some length the attitude and policy of Great Britain. He explained the reason for the obligations which Great Britain had undertaken in the Continent of Europe. He discussed Anglo-German relations and stated that Great Britain had no wish to isolate Germany, and that, if Germany wished, “a policy of cooperation” could be adopted at once. “British policy rests on twin foundations of purpose. One is determination to resist force. The other is our recognition of the world’s desire to get on with the constructive work of building peace” (No. 25).

June 3 to July 3, 1939 – Deterioration in the local situation at Danzig

With the increase of agitation in the Reich the local situation at Danzig rapidly became worse. On the 3rd June the President of the Danzig Senate made accusations against Polish customs inspectors (No. 26). The Polish Government on the 10th June replied with a denial of the accusations and a statement of the legal rights of Poland in relation to Danzig (No. 27). On the 27th June the Polish Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs told Sir H. Kennard, His Majesty’s Ambassador in Warsaw that a Freicorps was being formed in Danzig (No. 28), and on 28th and 30th June, and on the 1st July, Mr. Shepherd, His Majesty’s Consul-General in Danzig, reported upon military preparations in the city (Nos. 29, 31, 33). On the 30th June, in view of the gravity of the situation, Viscount Halifax suggested consultation between the British, French and Polish Governments for the co-ordination of their plans (No. 30). Meanwhile, the Polish Government maintained a restrained attitude (Nos. 32 and 34).

July 10 to 15, 1939 – British attitude towards developments in Danzig

On the 10th July, while the situation at Danzig appeared to be becoming critical, the Prime Minister defined the British attitude towards the Danzig problem in a statement in the House of Commons (No. 35).

He pointed out that it was before Poland had received any guarantee from Great Britain that the Polish Government, fearing to be faced with unilateral German action, had replied to the German proposals, by putting forward certain counter proposals, and that the cause of the Polish refusal to accept the German proposals was to be found in the character of these proposals and in the manner and timing of their presentation and not in the British guarantee of Poland.

On the 14th July Sir Nevile Henderson discussed with Baron von Weizsäcker, German State Secretary at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, a statement by one of the German Under-Secretaries that “Herr Hitler was convinced that England would never fight over Danzig.”

Sir Nevile Henderson repeated the affirmation already made by His Majesty’s Government that, in the event of German aggression, Great Britain would support Poland in resisting force by force (No. 36).

July 19 to August 2, 1939 – Temporary easing in the Danzig situation

After the tension in Danzig at the end of June there was a temporary lull in the situation.

The Acting British Consul-General at Danzig reported on the 19th July that Forster, the leader of the National Socialist party in Danzig, had stated, after an interview with Hitler, that “nothing will be done on the German side to provoke a conflict,” and that the Danzig question could “wait if necessary until next year or even longer” (No. 37).

On the 21st July Viscount Halifax instructed Mr. Norton, His Majesty’s Chargé d’Affaires at Warsaw, to impress upon the Polish Government the need for caution (No. 38). M. Beck replied, on the 25th July, that the Polish Government was equally anxious for a détente (No. 39).

On the previous day Forster had again stated that “the Danzig question could, if necessary, wait a year or more” (No. 40). On the 31st July and the 2nd August, however, Sir H. Kennard reported less hopefully about the position (Nos. 41 and 42).

August 4 to 16, 1939 – Further deterioration in the situation at Danzig

On the 4th August M. Beck told His Majesty’s Chargé d’Affaires at Warsaw that the Danzig Senate had that day informed Polish customs inspectors at four posts in Danzig that henceforward they would not be allowed to carry out their duties. The Polish Government took “a very serious view” of this step (No. 43). Similar news came from Mr. Shepherd at Danzig (No. 44). On the 9th August Sir H. Kennard reported that the Polish attitude was “firm but studiously moderate” (No. 45).

A day later, Sir H. Kennard reported to His Majesty’s Government a communication made by the German Government to the Polish Chargé d’Affaires at Berlin on the Danzig question, and the Polish reply to this communication. M. Beck drew the attention of Sir H. Kennard to “the very serious nature of the German démarche as it was the first time that the Reich had directly intervened in the dispute between Poland and the Danzig Senate” (No. 46).

The Polish Government in their reply to the German note verbale stated that they would “react to any attempt by the authorities of the Free City which might tend to compromise the rights and interests which Poland possesses there in virtue of her agreements, by the employment of such means and measures as they alone shall think fit to adopt, and will consider any future intervention by the German Government to the detriment of these rights and interests as an act of aggression” (No. 47).

Sir Nevile Henderson on the 15th August discussed with Baron von Weizsäcker the deterioration in the Danzig position, and pointed out that if the Poles “were compelled by any act of Germany to resort to arms to defend themselves, there was not a shadow of doubt that we would give them our full armed support. . . Germany would be making a tragic mistake if she imagined the contrary.”

Baron von Weizsäcker himself observed that “the situation in one respect was even worse than last year, as Mr. Chamberlain could not again come out to Germany.” Baron von Weizsäcker also discounted the character of Russian help to Poland and “thought that the U.S.S.R. would even in the end join in sharing the Polish spoils” (No. 48).

Meanwhile, on the 11th August, M. Burckhardt had a conversation with Hitler at Berchtesgaden at the latter’s request, in which the question of Danzig and the general European situation were discussed (No. 49). Viscount Halifax, who still hoped that Hitler might avoid war, advised the Polish Government to make it clear that they remained ready for negotiations over Danzig (Nos. 50 and 51).

August 24 to 27, 1939 – Treatment of the German minority in Poland

During the course of the correspondence outlined in this section, Sir H. Kennard reported that the German press campaign about the persecution of the German minority in Poland was a “gross distortion and exaggeration of the facts” (No. 52). On the 26th August Sir H. Kennard reported frontier incidents which had been provoked by the Germans. They had not caused the Poles to change their “calm and strong attitude of defence” (No. 53). Reports of unfounded German allegations against the Poles were also sent by Sir H. Kennard on the 26th and 27th August (Nos. 54 and 55).

August 24 to September 3, 1939 – Developments leading immediately to the outbreak of hostilities between Great Britain and Germany

On the 22nd August, after the publication of the news of von Ribbentrop’s visit to Moscow to sign a non-aggression pact with the U.S.S.R., the Prime Minister sent a personal letter to Hitler. Mr. Chamberlain once again gave a clear statement of the British obligations to Poland, and stated that “whatever may prove to be the nature of the German-Soviet Agreement, it cannot alter Great Britain’s obligation.” He added that “it has been alleged that, if His Majesty’s Government had made their position more clear in 1914, the great catastrophe would have been avoided. Whether or not there is any force in that allegation, His Majesty’s Government are resolved that on this occasion there shall be no such tragic misunderstanding” (No. 56).

On the 23rd August Sir Nevile Henderson reported his first interview with Hitler earlier in the day. Hitler was “excitable and uncompromising;” his language was “violent and exaggerated both as regards England and Poland.” Hitler observed, in reply to His Majesty’s Ambassador’s repeated warnings that direct action against Poland would mean war with Great Britain, that Germany had nothing to lose, and Great Britain much; that he did not desire war, but would not shrink from it if it was necessary, and that his people were much more behind him than last September (No. 57).

Hitler was calmer at a second talk, but no less uncompromising. He put the whole responsibility for war on Great Britain and maintained that Great Britain was “determined to destroy and exterminate Germany. He was, he said, 50 years old; he preferred war now to when he would be 55 or 60.” He said that “England was fighting for lesser races, whereas he was fighting only for Germany” (No. 58).

The German reply to the Prime Minister’s letter was given to His Majesty’s Ambassador on the 23rd August. Hitler stated that the British promise to assist Poland would make no difference to the determination of the Reich to safeguard German interests, and that the precautionary British military measures announced in the Prime Minister’s letter of 22nd August would be followed by the mobilization of the German forces (No. 60). (Text of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact is at No. 61).

Forster was declared by decree of the Danzig Senate, on the 23rd August Head of the State (Staatsoberhaupt) of the Free City of Danzig (No. 62). The Polish Government protested to the Senate against the illegality of the appointment (No. 63).

Speeches were given by the Prime Minister and Viscount Halifax on the Danzig and General German-Polish situation and the determination of Great Britain to honor British obligations to Poland (Nos. 64 and 65).

In view of the increasing tension in Danzig, M. Beck told Sir H. Kennard that he considered the situation “most grave,” and that he had asked the Polish Ambassador in Berlin to seek an immediate interview with the German State Secretary (No. 66). This interview could not, however, be arranged, since Baron von Weizsäcker was at Berchtesgaden, but the Polish Ambassador had an interview in the afternoon of the 24th August with Field-Marshal Göring. The Field-Marshal regretted that “his policy of maintaining friendly relations with Poland should have come to naught, and admitted that he no longer had influence to do much in the matter.” The Field-Marshal hinted that Poland should abandon her alliance with Great Britain, and left the Polish government with the impression that Germany was aiming at a free hand in Eastern Europe (No. 67).

On the 25th August Hitler sent for Sir Nevile Henderson and asked him to fly to London to “put the case” to His Majesty’s Government. The “case,” which included an offer of friendship with Great Britain, once the Polish question had been solved, was contained in a verbal communication made to His Majesty’s Ambassador (No. 68). During the discussion with Hitler, Sir Nevile Henderson stated once more that Great Britain “could not go back on her word to Poland,” and would insist upon a settlement by negotiation. Hitler refused to guarantee a negotiated settlement on the ground that “Polish provocation might at any moment render German intervention to protect German nations inevitable” (No. 69).

On the 25th August Viscount Halifax suggested to the Polish Government the establishment of a corps of neutral observers, who would enter upon their functions if it were found possible to open negotiations (No. 70). He also suggested the possibility of negotiating over an exchange of populations (No. 71). M. Beck raised no objection in principle to either proposal (No. 72).

On the 28th August Viscount Halifax informed the Polish Government through Sir H. Kennard that in the British reply to Hitler “a clear distinction” would be drawn between “the method of reaching agreement on German-Polish differences and the nature of the solution to be arrived at. As to the method, we (His Majesty’s Government) wish to express our clear view that direct discussion on equal terms between the parties is the proper means” (No. 73).

The reply of His Majesty’s Government, suggesting direct discussion between the German and Polish Governments, was presented to Hitler by Sir N. Henderson on the 28th August (No. 74). His Majesty’s Government stated they had “already received a definite assurance from the Polish Government that they are prepared to enter into discussions,” and that, if such direct discussion led, as they hoped, to agreement, “the way would be open to the negotiation of that wider and more complete understanding between Great Britain and Germany which both countries desire.”

In his interview of the 28th August with Hitler, Sir N. Henderson repeated the British readiness to reach an Anglo-German understanding, “but only on the basis of a peaceful and feely negotiated solution of the Polish question.” Sir Nevile Henderson pointed out to Hitler that “it lay with him (Herr Hitler) as to whether he preferred a unilateral solution which would mean war as regards Poland, or British friendship.” Herr Hitler, who said that “his army was ready and eager for battle,” would not answer at once whether he would negotiate directly with Poland (No. 75).

On the 29th August the Prime Minister once more explained in the House of Commons the British standpoint (No. 77).

At 7:15 p.m. on the 29th August Sir N. Henderson received from Hitler the German answer that the German Government was prepared to accept the British proposal for direct German-Polish negotiations, but counted on the arrival of a Polish plenipotentiary by the 30th August (No. 78). The British Ambassador remarked that the latter demand “sounded like an ultimatum,” but, after some heated remarks, both Hitler and von Ribbentrop assured the Ambassador “that it was only intended to stress the urgency of the moment” (No. 79). The interview was “of a stormy character.” Sir N. Henderson thought that Hitler was “far less reasonable” than on the 28th August (No. 80).

At 4 A.M. on the 30th August Sir N. Henderson, on instructions from His Majesty’s Government, informed the German Government that it would be “unreasonable to expect the British Government to produce a Polish representative in Berlin” by the 30th August and that “the German Government must not expect this” (Nos. 81, 82, 83).

Sir H. Kennard also reported his opinion that the Polish Government could not be induced to send a representative immediately to Berlin to discuss a settlement on the basis proposed by Hitler. “They would certainly sooner fight and perish rather than submit to such humiliation, especially after the examples of Czecho-Slovakia, Lithuania and Austria” (No. 84). On this same day the Polish government gave their assurance, in reply to advice from Viscount Halifax, to avoid any kind of provocation (No. 85), that they had no intention of provoking any incidents, in spite of the provocation at Danzig, which was becoming “more and more intolerable” (No. 86).

At 2:45 p.m. and again at 5:30 p.m. on the 30th August His Majesty’s Government instructed Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government of the representations which the British Government had made in Warsaw for the avoidance of all frontier incidents and urged the German Government to reciprocate (Nos. 83 and 87). They repeated at 6:50 p.m., in view of the German insistence on the point, that it was “wholly unreasonable” for the German Government to insist upon the arrival in Berlin of a Polish representative with full powers to receive German proposals, and that they could not advise the Polish Government in this sense. They suggested the normal procedure of giving the Polish Ambassador the German proposals for transmission to Warsaw (No. 88).

At midnight on the 30th-31st August Sir N. Henderson handed to von Ribbentrop the full British reply to the German letter of the 29th August (No. 78). The reply noted the German Government’s acceptance of the British proposal for direct German-Polish discussions and of the “position of His Majesty’s Government as to Poland’s vital interests and independence.”

The reply also noted that the German Government accepted “in principle the condition that any settlement should be made the subject of an international guarantee.” His Majesty’s Government stated that they were informing the Polish Government of the German Government’s reply. “The method of contact and arrangements for discussions must obviously be agreed with all urgency between the German and Polish Governments, but in His Majesty’s Government’s view it would be impracticable to establish contact so early as today (i.e., the 30th August) (No. 89).

The British reply was also telegraphed to the Polish Government, and Viscount Halifax hoped that “provided the method and general arrangement for discussions can be satisfactorily agreed,” the Polish Government, which had authorized His Majesty’s Government to say that they were prepared to enter into direct discussions, would be ready to do so without delay (No. 90).

In his interview at midnight the 30th-31st August with von Ribbentrop, Sir N. Henderson suggested that the German Government should adopt the normal procedure of making contact with the Polish Government, i.e., that when the German proposals were ready the Polish Ambassador should be invited to call and to receive these proposals “for transmission to this Government with a view to the immediate opening of negotiations.”

“Herr von Ribbentrop’s reply was to produce a lengthy document which he read out in German aloud at top-speed.” When His Majesty’s Ambassador asked for the text of the proposals in the document, he was told that it was “now too late,” as a Polish representative had not arrived in Berlin by midnight (the 30th-31st August). Sir N. Henderson described this procedure as an “ultimatum,” in spite of the assurances previously given by the German Government. He asked why von Ribbentrop could not adopt the normal procedure, give him a copy of the proposals, and ask the Polish Ambassador to call on him (Herr von Ribbentrop) to receive them. “In the most violent terms Herr von Ribbentrop said that he would never ask the Polish Ambassador to visit him,” though he hinted that it might be different if the Polish Ambassador asked for an interview (No. 92).

On hearing of the reply of His Majesty’s Government to the German Government (No. 89) on the subject of direct German-Polish negotiations, M. Beck said that he would do “everything possible to facilitate the efforts of His Majesty’s Government.” He promised the “considered reply of his Government” by midday on the 31st August (No. 93). Later on the 31st August Viscount Halifax advised the Polish Government immediately to instruct the Polish Ambassador in Berlin to say that he was ready to transmit to his Government any proposals made by the German Government so that they (the Polish Government) “may at once consider them and make suggestions for early discussions” (No. 95).

At 6:30 p.m. on the 31st August Sir H. Kennard communicated to London the formal Polish confirmation of the readiness of the Polish Government to enter into direct discussions with the German Government on the basis proposed by Great Britain (No. 97). M. Beck said that “he would now instruct M. Lipski (Polish Ambassador in Berlin) to seek an interview either with the (German) Minister for Foreign Affairs or the State Secretary” in order to establish contact for the initiation of direct discussions, but that the Polish Ambassador would not be authorized to receive a document containing the German proposals, since, “in view of past experience, it might be accompanied by some sort of ultimatum.” In M. Beck’s view “it was essential that contact should be made, in the first instance,” for the discussion of details “as to where, with whom, and on what basis negotiations should be commenced” (No. 96).

It was not until 9:15 p.m. on the 31st August that the German Government gave Sir N. Henderson a copy of their proposals, which had been read to him so rapidly by von Ribbentrop on the previous night. The German Government stated that the noted contained the sixteen points of their proposed settlement, but that, as the Polish plenipotentiary, with powers “not only to discuss but to conduct and conclude negotiations,” had not arrived in Berlin, they regard their proposals as “to all intents and purposes rejected” (No. 98).

At 11 p.m. Viscount Halifax telephoned to Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government that the Polish Government was taking steps to establish contact with them through the Polish Ambassador in Berlin (No. 99). At 9 p.m. British summer time the German Government had, however, broadcast their proposals together with the statement that they regarded them as having been rejected. They had, however, never been communicated to the Polish Government and all means of communication between the Polish Ambassador in Berlin and the Polish Government had been cut off.

As a final attempt to meet the German demands, Viscount Halifax telegraphed to Sir H. Kennard in the night of the 31st August 1st September his view that the Polish Ambassador in Berlin might receive a document for transmission to his Government and might say that “(a) if it contained anything like an ultimatum, the Polish Government would certainly be unable to discuss on such a basis; and (b) that, in any case, in the view of the Polish Government, questions as to the venue of the negotiations, the basis on which they should be held, and the persons to take part in them, must be discussed and decided between the two Governments” (No. 100).

In answer to this telegram, Sir H. Kennard replied on the 1st September that M. Lipski “had already called on the German Foreign Minister at 6:30 p.m.” on the 31st August. “In view of this fact, which was followed by the German invasion of Poland at dawn today (1st September); it was clearly useless for me to take the action suggested” (No. 101).

These facts were announced to the House of Commons by the Prime Minister on the 1st September (No. 105). A further “explanatory note, upon the actual course of events,” reprinted from White Paper (Misc. No. 8 (1939), Crud. 6102) (No. 104) should be read in connection with Hitler’s version of events as given in his speech of the 1st September to the Reichstag (No. 106) and in his proclamation to the German army (No. 107).

On the 1st September Forster announced in a proclamation to the people of Danzig the reunion of Danzig with the Reich. He telegraphed an account of his action to Hitler, who replied at once accepting the reunion and ratifying the so-called legal act by which it was brought about (No. 108).

On the 1st September, after His Majesty’s Government had received news of the German invasion of Poland Viscount Halifax instructed Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government that the Governments of the United Kingdom and France considered that the German action had “created conditions (viz., an aggressive act of force against Poland threatening the independence of Poland) which call for the implementation by the Governments of the United Kingdom and France of the undertaking to Poland to come to her assistance.”

Unless the German Government suspended all aggressive action against Poland, and promptly withdrew their forces from Polish territory, His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom would “without hesitation fulfill their obligations to Poland.” Sir N. Henderson was authorized to explain, if asked, that this communication was “in the nature of a warning,” and was “not to be considered as an ultimatum,” but Viscount Halifax added, for Sir. N. Henderson’s own information, that, “if the German reply is unsatisfactory, the next stage will be either an ultimatum with time-limit or an immediate declaration of war” (Nos. 109 and 110).

On the night of the 1st -2nd September Sir N. Henderson reported that he had made the necessary communication to von Ribbentrop at 9:30 p.m. and had asked for an immediate answer. Herr von Ribbentrop replied that he would submit the communication to Hitler (No. 111). Meanwhile, on the 1st September, the Polish Government announced to His Majesty’s Government that, although the Polish Ambassador in Berlin had seen von Ribbentrop at 6:30 p.m. on the 31st August, and had expressed the readiness of the Polish Government to enter into direct negotiations, Polish territory had been invaded, and the Polish Government had therefore been compelled to break off relations with Germany (No. 112) (see also Nos. 113 and 115). At 10:50 a.m. on the 1st September Viscount Halifax sent for the German Chargé d’Affaires in London, drew his attention to the reports which had reached His Majesty’s Government about German action against Poland and informed him that these reports “created a very serious situation” (No. 114).

The Prime Minister on the 2nd September made a statement in the House of Commons, in the course of which he said that no answer had been received to the message sent to the German Government on the 1st September, requesting the cessation of German aggression and the withdrawal of German troops from Poland. The Prime Minister also informed the House of proposals put forward by Italian Government for a cessation of hostilities, but made it clear that His Majesty’s Government could not take part in any conference unless German aggression ceased and German troops were withdrawn from Poland (No. 116).

At 5 a.m. 3rd September Sir N. Henderson was instructed to ask for an interview at 9 a.m. with von Ribbentrop and to inform him that, although His Majesty’s Government had warned the German Government of the results which would follow if Germany did not suspend all aggressive action against Poland, no answer had been received from the German Government. His Majesty’s Government therefore stated that unless satisfactory assurances were received from the German Government not later than 11 a.m. a state of war would exist between the United Kingdom and German (No. 118).

At 11:20 a.m. on the 3rd September the German Government replied with a statement of their case, concluding with the suggestion that His Majesty’s Government desired the destruction of the German people, and with the words, “we shall answer any aggressive action on the part of England with the same weapons and in the same form” (No. 119). Shortly afterwards the Prime Minister announced in the House of Commons that Great Britain was at war with Germany (No. 120). Hitler addressed the German people and the German army on 3rd September (No. 121). The Prime Minister broadcast to the German People on 4th September (No. 122).

–End of Excerpt–

Excerpt from The Campaign in Poland 1939 (Silver Spring: Dale Street Books, 2014), Originally published in 1941 at the United States Military Academy.

Excerpt from The Campaign in Poland 1939 (Silver Spring: Dale Street Books, 2014), Originally published in 1941 at the United States Military Academy.