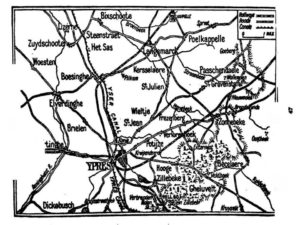

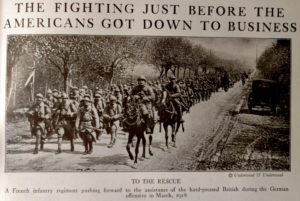

Excerpt from 1914 by John French, Viscount of Ypres, first Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Forces. ebook version here http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24538/24538-h/24538-h.htm

Excerpt from 1914 by John French, Viscount of Ypres, first Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Forces. ebook version here http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24538/24538-h/24538-h.htm

[…] THE BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

I have thought fit to interrupt my narrative here to devote some pages to the composition of the original Expeditionary Force. The First Expeditionary Force consisted of the First Army Corps (1st and 2nd Divisions) under Lieut.-Gen. Sir Douglas Haig; the Second Army Corps (3rd and 5th Divisions) under Lieut.-Gen. Sir James Grierson (who died shortly after landing in France and was succeeded by Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien), and the Cavalry Division under Major-Gen. E. H. H. Allenby. To these must be added the 19th Infantry Brigade, which, at the opening of our operations in France, was employed on our Lines of Communication. The original Expeditionary Force was subsequently augmented by the 4th Division, which detrained at Le Cateau on August 25th. The 4th Division and the 19th Infantry Brigade were, on the arrival of Gen. Pulteney in France, on August 30th, formed into the Third Army Corps, to which the 6th Division was subsequently added.

For the purpose of convenient reference, I have included in this chapter the composition of the 6th Division, which joined us on the Aisne, and of the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division, which came into line with the original Expeditionary Force in Belgium in the opening stages of the First Battle of Ypres; as also of the Lahore Division of the Indian Corps, which likewise took part in the Battle of Ypres.

THE FIRST EXPEDITIONARY FORCE.

General Officer Commanding-in-Chief: Field-Marshal Sir J. D. P. French.

Chief of the General Staff: Lieut.-Gen. Sir A. J. Murray.

Adjutant-General: Major-Gen. Sir C. F. N. Macready.

Quartermaster-General: Major-Gen. Sir W. R. Robertson.

First Army Corps: Lieut.-Gen. Sir Douglas Haig.

1st Division: Major-Gen. S. H. Lomax, wounded October 31st, replaced by Brig.-Gen. Landon (temp.), then by Brig.-Gen. Sir D. Henderson.

1st Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. F. I. Maxse, succeeded by Brig.-Gen. FitzClarence, V.C. (killed, November 11th). Col. McEwen then took command. Later on, Col. Lowther was appointed to command the Brigade.

1st Batt. Coldstream Guards.

1st Batt. Scots Guards.

London Scottish (joined Brigade in November).

1st Batt. Royal Highlanders (the Black Watch).

2nd Batt. Royal Munster Fusiliers (cut to pieces at Etreux, August 29th, replaced by 1st Batt. Cameron Highlanders).

2nd Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. E. S. Bulfin, wounded November 1st, succeeded by Col. Cunliffe-Owen (temp.). Brig.-Gen. Westmacott took command November 23rd.

2nd Batt. Royal Sussex Regt.

1st Batt. Northampton Regt.

1st Batt. N. Lancs Regt.

2nd Batt. K.R.R.

3rd Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. H. J. S. Landon, appointed to command the Division after October 31st, Col. Lovett taking command of Brigade. Brig.-Gen. R. H. K. Butler was appointed to command the Brigade November 13th.

1st Batt. The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regt. (cut up October 31st, replaced by 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers).

1st Batt. S. Wales Borderers.

1st Batt. Gloucester Regt.

2nd Batt. Welsh Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

“C” Squadron 15th Hussars.

1st Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

23rd & 26th Field Cos.

1st Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXV. Brigade—113, 114, 115.

XXVI. Brigade—116, 117, 118.

XXIX. Brigade—46, 51, 54.

XLIII. Brigade (Howitzer)—30, 40, 57.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—26. 1st Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Field Ambulances.

2nd Division: Major-Gen. C. C. Monro.

4th (Guards) Brigade: Brig.-Gen. R. Scott-Kerr, wounded September 1st and succeeded by Brig.-Gen. the Earl of Cavan (arrived September 18th).

2nd Batt. Grenadier Guards.

3rd Batt. Coldstream Guards.

2nd Batt. Coldstream Guards.

1st Batt. Irish Guards.

1st Herts (T.F.) (joined Brigade about November 10th).

5th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. R. C. B. Haking, wounded on September 16th; succeeded by Lieut.-Col. Westmacott until Haking returned on November 20th.

2nd Batt. Worcester Regt.

2nd Batt. Highland L.I.

2nd Batt. Oxf. & Bucks L.I.

2nd Batt. Connaught Rangers. (2nd Connaughts were amalgamated with their 1st Batt. at the end of November and replaced in the Brigade by 9th H.L.I. (Glasgow Highlanders).)

6th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. R. H. Davies, invalided in September; succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Fanshawe, September 13th.

1st Batt. The King’s (Liverpool) Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Berks Regt.

2nd Batt. S. Staffs Regt.

1st Batt. K.R.R.

Divisional Cavalry:

“B” Squadron 15th Hussars.

2nd Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

5th & 11th Field Cos.

2nd Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXIV XXXIV. Brigade—25, 50, 70.

XXXVI. Brigade—15, 48, 71.

XLI. Brigade—9, 16, 17.

XLIV. Brigade (Howitzer)—47, 56, 60.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—35. 2nd Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 4th, 5th & 6th Field Ambulances.

Second Army Corps: Lieut.-Gen. Sir James Grierson, died August 17th; succeeded by Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien.

3rd Division: Major-Gen. Hubert I. W. Hamilton, killed October 14th; Major-Gen. Mackenzie in command till end of October; then Major-Gen. Wing till November 6th; then Major-Gen. Haldane.

7th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. F. W. N. McCracken

3rd Batt. Worcester Regt.

1st Batt. Wilts Regt.

2nd Batt. S. Lancs Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Irish Rifles.

8th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. B. J. C. Doran, invalided October 23rd; Brig.-Gen. Bowes took over command.

2nd Batt. Royal Scots.

2nd Batt. Royal Irish Regt. (Battalion cut up at Le Pilly, October 20th; became G.H.Q. troops, replaced by 2nd Suffolks.)

4th Batt. Middlesex Regt.

1st Batt. Gordon Highlanders. (Employed as G.H.Q. troops during September, being replaced by 1st Devons, but rejoined Brigade at beginning of October.)

9th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. F. C. Shaw, wounded November 12th; succeeded by Lieut.-Col. Douglas Smith, Royal Scots Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Northumberland Fusiliers.

4th Batt. Royal Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Lincolnshire Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Divisional Cavalry:

“A” Squadron 15th Hussars.

3rd Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

56th & 57th Field Cos.

3rd Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXIII. Brigade—107, 108, 109.

- Brigade—6, 23, 49.

XLII. Brigade—29, 41, 45.

XXX. Brigade (Howitzer)—128, 129, 130.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—48.

3rd Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 7th, 8th, & 9th Field Ambulances.

5th Division: Major-Gen. Sir Charles Fergusson, invalided October 22nd; succeeded by Major-Gen. Morland.

13th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. G. J. Cuthbert, invalided about the end of September; succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Hickie, who went sick October 13th, Col. Martyn getting command (temp.).

2nd Batt. K.O. Scottish Borderers.

2nd Batt. (Duke of Wellington’s) West Riding Regt.

1st Batt. Royal West Kent Regt.

2nd Batt. K.O. Yorkshire L.I.

14th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. S. P. Rolt, invalided October 29th; succeeded by Brig.-Gen. F. S. Maude.

2nd Batt. Suffolk Regt. (replaced by 1st Devons at the beginning of October, and became G.H.Q. troops).

1st Batt. East Surrey Regt.

1st Batt. Duke of Cornwall’s L.I.

2nd Batt. Manchester Regt.

15th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. Count A. E. W. Gleichen.

1st Batt. Norfolk Regt.

1st Batt. Cheshire Regt.

1st Batt. Bedford Regt.

1st Batt. Dorset Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

“A” Squadron 19th Hussars.

Royal Engineers:

17th & 59th Field Cos.

5th Cyclist Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

- Brigade—11, 52, 80.

XXVII. Brigade—119, 120, 121.

XXVIII. Brigade—122, 123, 124.

VIII. Brigade (Howitzer)—37, 61, 65.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—108.

5th Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 13th, 14th, & 15th Field Ambulances.

19th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. L. G. Drummond, succeeded early in September by Brig.-Gen. F. Gordon. [Note.—This Brigade was formed from units on Lines of Communication, and was attached successively to the Cavalry Division, Second Corps and Fourth Division during the retreat from Mons and advance to the Aisne. In the Flanders fighting of October-November, 1914, it worked with the Sixth Division.]

2nd Batt. Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Scottish Rifles.

1st Batt. Middlesex Regt.

2nd Batt. Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

19th Field Ambulance.

Cavalry Division: Major-Gen. E. H. H. Allenby, took command of the Cavalry Corps on its formation in October, Brig.-Gen. De Lisle taking command of the 1st Cavalry Division.

1st Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. C. J. Briggs.

2nd Dragoon Guards. 5th Dragoon Guards.

11th Hussars.

2nd Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. H. De B. De Lisle, transferred to command 1st Cavalry Division in October and succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Mullins.

4th Dragoon Guards.

9th Lancers.

18th Hussars (Queen Mary’s Own).

3rd Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. Hubert De La Poer Gough.

4th Hussars.

5th Lancers.

16th Lancers.

4th Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. Hon. C. E. Bingham.

Household Cavalry (Composite Regt.).

6th Dragoon Guards. 3rd Hussars.

5th Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. Sir Philip P. W. Chetwode.

12th Lancers.

20th Hussars.

2nd Dragoons (Scots Greys).

Royal Horse Artillery:

Batteries—”D,” “E,” “I,” “J,” “L” (“L” Battery went home to refit after Néry (September 1st), and was replaced by “H,” R.H.A., which arrived about the middle of September).

Royal Engineers:

1st Field Squadron. 1st Signal Squadron.

[Note.—In September the 2nd Cavalry Division was formed, consisting at first of the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades under Major-Gen. Gough, Brig.-Gen. Vaughan taking command of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade. With these brigades were “D” and “E” Batteries, R.H.A. In October the 4th Cavalry Brigade was transferred to the 2nd Cavalry Division, as was also “J” Battery, R.H.A. The 2nd Cavalry Division had the 2nd Field Squadron R.E. and 2nd Signal Squadron.]

R.A.M.C.: corresponding Cavalry Field Ambulances.

Royal Flying Corps: Brig.-Gen. Sir David Henderson.

Aeroplane Squadrons Nos. 2, 3, 4, and 5.

4th Division: Major-Gen. T. D. O. Snow, invalided September; succeeded by Major-Gen. Sir H. Rawlinson, who was transferred to 4th Army Corps early in October and replaced by Major-Gen. H. F. M. Wilson.

10th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. J. A. L. Haldane, appointed to command 3rd Division, November 6th; succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Hull.

1st Batt. Royal Warwickshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Seaforth Highlanders.

1st Batt. Royal Irish Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

11th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. A. G. Hunter-Weston.

1st Batt. Somersetshire L.I.

1st Batt. Hampshire Regt.

1st Batt. E. Lancs Regt.

1st Batt. Rifle Brigade.

12th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. H. F. M. Wilson, in command of the 4th Division in October, and on promotion succeeded by Col. F. G. Anley.

1st Batt. K.O. (R. Lancaster) Regt.

2nd Batt. Lancashire Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Essex Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

“B” Squadron 19th Hussars.

4th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

7th & 9th Field Cos.

4th Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XIV. Brigade—39, 68, 88.

XXIX. Brigade—125, 126, 127.

XXXII. Brigade—27, 134, 135.

XXXVII. Brigade—31, 35, 55.

Heavy Battery, R.G.A.—31.

R.A.M.C.: 10th, 11th, & 12th Field Ambulances.

Lines of Communication and Army Troops:

1st Batt. Devonshire Regt. (transferred to 8th Brigade about middle of September, later to 14th Brigade).

1st Batt. Cameron Highlanders (replaced 2nd Munsters in 1st Brigade about September 6th).

[Note.—The 28th London (Artists’ Rifles), 14th London (London Scottish), 6th Welsh and 5th Border Regt. were all in France before the end of the First Battle of Ypres, as was also the Honourable Artillery Company. These battalions were all at first on Lines of Communication.]

6th Division: Major-Gen. J. L. Keir.

16th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. C. Ingouville-Williams.

1st Batt. East Kent Regt. (The Buffs).

1st Batt. Leicestershire Regt.

1st Batt. Shropshire L.I.

2nd Batt. York and Lancaster Regt.

17th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. W. R. B. Doran.

1st Batt. Royal Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Leinster Regt.

1st Batt. N. Staffs Regt.

3rd Batt. Rifle Brigade.

18th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. W. N. Congreve, V.C.

1st Batt. West Yorks Regt.

2nd Batt. Notts and Derby Regt.

1st Batt. East Yorks Regt. (the Sherwood Foresters).

2nd Batt. Durham. L.I.

Divisional Cavalry:

“C” Squadron 19th Hussars.

6th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

12th & 38th Field Cos.

6th Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

- Brigade—21, 42, 53.

XXIV. Brigade—110, 111, 112.

XXXVIII. Brigade—24, 34, 72.

XII. Brigade (Howitzer)—43, 86, 87.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—24. 6th Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 16th, 17th & 18th Field Ambulances.

7th Infantry Division: Major-Gen. T. Capper.

20th Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. H. G. Ruggles-Brise.

1st Batt. Grenadier Guards.

2nd Batt. Border Regt.

2nd Batt. Scots Guards.

2nd Batt. Gordon Highlanders.

21st Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. H. E. Watts.

2nd Batt. Bedfordshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Scots Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Yorkshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Wiltshire Regt.

22nd Infantry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. S. T. B. Lawford.

2nd Batt. The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Warwickshire Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

1st Batt. S. Staffs Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

Northumberland Yeomanry (Hussars).

7th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

54th & 55th Field Cos.

7th Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.H.A. Batteries—”F” and “T.”

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXII. Brigade—104, 105, 106.

XXV. Brigade—12, 35, 58.

Heavy Batteries R.G.A.—111, 112.

R.A.M.C.: 21st, 22nd and 23rd Field Ambulances.

3rd Cavalry Division: Major-Gen. The Hon. Julian Byng.

6th Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. E. Makins.

3rd Dragoon Guards (joined the Division early in November).

North Somerset Yeomanry (attached to the Brigade before the end of First Battle of Ypres).

1st Dragoons (The Royals).

10th Hussars.

7th Cavalry Brigade: Brig.-Gen. C. T. McM. Kavanagh.

1st Life Guards.

2nd Life Guards.

Royal Horse Guards (the Blues).

Royal Horse Artillery:

Batteries “C” and “K.”

Royal Engineers:

3rd Field Squadron.

R.A.M.C.: 6th, 7th and 8th Cavalry Field Ambulances.