Excerpt from A History of the Great War by Arthur Conan Doyle (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1917), Vol. Two, pp. 48, 49 (describing the first mass gas attack on the Western Front).

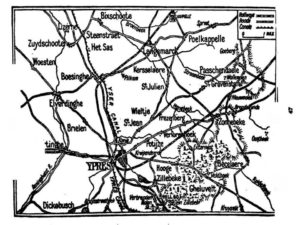

[…] Up to the third week of April the enemy opposite the French had consisted of the Twenty-sixth Corps, with the Fifteenth Corps on the right, all under the Duke of Württemberg, whose headquarters were at Thielt. There were signs, however, of secret concentration which had not entirely escaped the observation of the Allied aviators, and on April 20 and 21 the German guns showered shells on Ypres. About 5 p.m. upon Thursday, April 22, a furious artillery bombardment from Bixschoote to Langemarck began along the French lines, including the left of the Canadians, and it was reported that the Forty fifth French Division was being heavily attacked. At the same time a phenomenon was observed which would seem to be more in place in the pages of a romance than in the record of an historian. From the base of the German trenches over a considerable length there appeared jets of whitish vapour, which gathered and swirled until they settled into a definite low cloud-bank, greenish-brown below and yellow above, where it reflected the rays of the sinking sun. This ominous bank of vapour, impelled by a northern breeze, drifted swiftly across the space which separated the two lines. The French troops, staring over the top of their parapet at this curious screen which ensured them a temporary relief from fire, were observed suddenly to throw up their hands, to clutch at their throats, and to fall to the ground in the agonies of asphyxiation. Many lay where they had fallen, while their comrades, absolutely helpless against this diabolical agency, rushed madly out of the mephitic mist and made for the rear, over-running the lines of trenches behind them. Many of them never halted until they had reached Ypres, while others rushed westwards and put the canal between themselves and the enemy. The Germans, meanwhile, advanced, and took possession of the successive lines of trenches, tenanted only by the dead garrisons, whose blackened faces, contorted figures, and lips fringed with the blood and foam from their bursting lungs, showed the agonies in which they had died. Some thousands of stupefied prisoners, eight batteries of French field-guns, and four British 4.7’s, which had been placed in a wood behind the French position, were the trophies won by this disgraceful victory. The British heavy guns belonged to the Second London Division, and were not deserted by their gunners until the enemy’s infantry were close upon them, when the strikers were removed from the breech-blocks and the pieces abandoned. It should be added that both the young officers present, Lieuts. Sandeman and Hamilton Field, died beside their guns after the tradition of their corps. […]