“The last campaign of the World War was a fitting climax to a struggle which had endured already for more than three years and had surpassed all previous contests recorded in human history. In the final phase more than six millions of men, representing seven nations, fought for 235 days on a front of 250 miles from the North Sea to the Moselle, from the outer defences of Metz to the ruins of Nieuport. And the struggle was not limited to the west front. While Germany met her ancient foes in decisive contest on the battlefields of France, Italian armies first repulsed then crushed the Austrians on the Piave; Serbian, Greek, French, British, and Italian troops fought Bulgarians in Albania and Macedonia, and British troops overwhelmed the Turk on the Plain of Armageddon. Two continents furnished the battlefields, and five, reckoning Australia, supplied the combatants.

“The last campaign of the World War was a fitting climax to a struggle which had endured already for more than three years and had surpassed all previous contests recorded in human history. In the final phase more than six millions of men, representing seven nations, fought for 235 days on a front of 250 miles from the North Sea to the Moselle, from the outer defences of Metz to the ruins of Nieuport. And the struggle was not limited to the west front. While Germany met her ancient foes in decisive contest on the battlefields of France, Italian armies first repulsed then crushed the Austrians on the Piave; Serbian, Greek, French, British, and Italian troops fought Bulgarians in Albania and Macedonia, and British troops overwhelmed the Turk on the Plain of Armageddon. Two continents furnished the battlefields, and five, reckoning Australia, supplied the combatants.

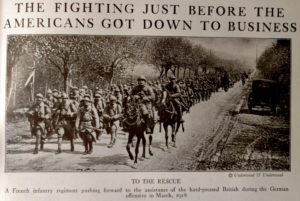

“But it was the issue of contest in France which decided the fate of the world and the question of victory and defeat in the great struggle. And in this contest, which French historians already regard as a single engagement and describe as the “Battle of France,” all the previous western campaigns were repeated on a hugely increased scale. When the Germans crushed the British Fifth Army in March 1918, they swept forward over all the territory which had been gained and lost in the First Battle of the Somme and the subsequent “Hindenburg” Retreat.

“When in April German effort turned north, it was on the fields of Flanders, the scene of the three great struggles about Ypres, that one more tremendous battle was fought. In April, before the war drifted northward, too, the German storm once more reached the foot of Vimy Ridge. In May, when [Erich von] Ludendorff faced southward, a new conflict broke out upon the battlefields on the Craonne Plateau, where [Alexander von] Kluck had checked the French and British advance from the Marne in 1914, where Ludendorff had broken the Nivelle offensive in 1917.

“In July the last German attack stormed at the lines held by the French in Champagne, since the first great offensive, that of September, 1915, and in the same hour passed the Marne at the towns where the armies of [Karl von] Bulow and Kluck had crossed and recrossed that stream in the days of the First Battle of the Marne. Indeed, the Second Battle of the Marne in July, 1918, was in so many respects a replica of the First in September, 1914, that history affords no parallel more striking.

“When at last the tide had turned, the Allied advance in July followed the roads used by Maunoury, French, and Franchet d’Esperey after the First Marne, while the British victories of August and September were won on the fields of the First Somme, and the battle names of these two months recalled with glorious exactitude the places made famous and terrible by the campaign of two years before. In the closing days of September, moreover, the first American army to enter the conflict struggled forward over the hills and through the villages which had seen in 1916 the beginning of the German offensive before Verdun.

“With the coming of October, the whole character of the campaign changed. At last one saw the realization of all the various and ambitious plans for allied operations in the past. The British, emerging from the Ypres salient, swept the Germans from the Belgian coast and turned them out of the industrial cities of the French north. The French and British on the sides of the Noyon salient realized the hopes of their commanders in 1916 and 1917, and entered St. Quentin and Laon, Cambrai, and Douai. Still to the eastward the French and the Americans, on either side of the Argonne between Rheims and Verdun, repeated on a widened front the attack of Joffre in September 1915, and achieved supreme success. lastly, in the St. Mihiel salient, the American First Army in its initial engagement put into successful operation the plans of the French in the winter of 1914-15 and, by abolishing the salient, closed the gap in the eastern armour of France.

“Flanders, Artois, Picardy, Ile-de-France, Champagne, and Lorraine were, in their turn, scenes of new contests whose extent of front surpassed the limits of ancient provides, whose circumstances recalled the history of previous campaigns, and disclosed in success the purposes and plans of Allied commanders, which had been in the past imperfectly realized or totally wrecked. And as a final dramatic detail, when at last the Armistice came, King Albert was approaching his capital at the head of a Belgian army; Canadian troops had entered Mons, where British participation in the struggle had begun; French armies were in Sedan, the town for ever associated with the French disasters of 1870; and a Franco-American offensive was just about to break out to the east of Metz, over the ground which had seen the first French dash into the “Lost Provinces” and the opening reverse at Morhange.

“Nor was the drama alone splendid in its magnitude. Every element of suspense, surprise, intensity was present to hold the attention of the world, neutral and engaged alike; and so terrible was the ordeal that, the moment of victory once passed, conqueror and conquered alike sank back exhausted by the strain beyond that which had ever before been placed upon the millions in line, and behind the line, who constituted nations at war.

“For history, moreover–which has attached to the Hundred Days of Napoleon a lasting significance as affording a standard of measurement for the rise and fall of one of the world’s great figures–there must be hardly less meaning in the span of Ludendorff, longer by twenty days only, which saw the greatest of German military leaders three times on the edge of supreme victory and, on the final day, overtaken by swift defeat, ordering a second retreat from the Marne; and this retreat, in barely more than another hundred days, would end in surrender after decisive defeat, which alone prevented the supreme disaster of a Waterloo twentyfold magnitude.

“Since Napoleon fell, no soldier had known such intoxicating success as came to Ludendorff in March, in April, and again in May; while between March 26th and November 11th, Foch–first in defeat prepared by his predecessors, and then in victory organized by his own genius–wrote the most brilliant and far-shining page in all military history, and earned the right to rank as a soldier with the great Emperor, who had been his model.

“In less than eight months, the finest army in size, equipment, and training ever put into the field by a civilized nation was transformed–after initial victories which had no parallel in this or any other war, after conquests of ground, captures of guns, harvestings of prisoners unequalled in all the past campaigns of the war–into a broken and beaten host, incapable of warding off the final blow, defeated beyond hope of recovery, still retaining a semblance of its ancient courage and in parts a shadow of its traditional discipline, but incapable of checking its pursuers, of maintaining its positions, of long postponing that ultimate disaster, already prepared, when an armistice–incomprehensible even to the beaten army, by reason of the completeness of the surrender–saved the conquered from the otherwise inescapable rout.” Frank H. Simonds, History of the World War, Vol. 5 (New York: Doubleday Page & Company, 1920), pp. 3-7.